How do you know what impact the product you are developing will have? Your initial answer to this question might be: You don’t know and, unless you are clairvoyant, you can’t know. If you consider impact something that can only occur once a product is finished, you would be right to say this.

However, the Mingei team believes that a product, or to be more precise, the project delivering the product, can have significant impact during its development phase. We use the same definition of impact as Europeana uses in their Impact Playbook for Museums, Libraries, Archives and Galleries. Impact consists of “the changes that occur for stakeholders or in society as a result of activities (for which the organisation is accountable.” In this context, we focus on impact that might occur as a result of growing awareness amongst our target audiences, the impact of our scientific publications on the academic community, and the organisational learning that happens as a result of Mingei collaborations.

We decided to measure and work to optimise impact throughout the lifecycle of the project, rather than merely measuring the end result. While developing our tools, our understanding of their capabilities will shift and grow, making it possible to better understand the potential impact and to take action to optimise this potential as part of our development process. So, how are we doing this?

Work as a team

Rather than appointing one or two people in charge of monitoring impact, we decided to take a more proactive approach and work in several small teams to actively improve the impact our work may have on our key stakeholders. Our heritage partners are particularly important in this process, as they are most closely in contact with (some of) the potential future users of our tools.

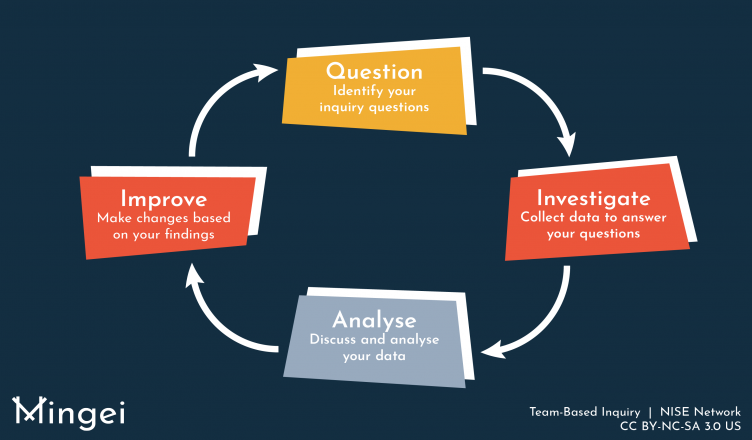

To make sure we progress in pace with the project, keeping our research relevant for whatever phase we are in, we are using a method called Team Based Inquiry, or TBI. TBI was developed by the Nanoscience Informal Science Education Network and was initially used to continuously assess and improve (nano)science education projects. It makes use of a cyclical process, consisting of four steps: question, investigate, analyse and improve. This allows you to be topical and progress in your research, while also aiming for continuous improvements.

We will use the TBI cycle throughout the project, where our heritage partners will each be leading their own cyclical processes, with input and contributions from technical partners when needed. During the first phases of the Mingei project, we will focus on developing relationships with our key stakeholders, as well as better understanding their needs. Later on, the same approach will be used to focus on skills development. What skills do key players have, or need, that can help make the Mingei tools a success? By better understanding key stakeholders and their skills, we can together work towards improving the tools we will offer them.

Monitoring impact

Finally, we will also be monitoring the impact the Mingei project will have on our heritage partners. Not only because they will be important users of the Mingei tools in their own right, but also because by better understanding the impact the project has on them, we will be able to optimise our tools for use by other heritage professionals. Each heritage partner has finished their first TBI cycle, delving into a question they deemed relevant to their situation at that time. Although these first cycles were seen as a test run of sorts, the results were very promising.