Thematic tourism

An Island Full of surprises

About mastic

Mastiha, or mastic, is a product from the mastic tree, which exclusively grows in the south-west of Chios Island in Greece. This HC is therefore highly localised (indigenous craft) and part of the fabric of local life. The 24 villages from where mastiha is harvested are known as Mastihochoria, or Mastic Villages, their name being an indication of the importance of mastiha for the region. It is an outdoor craft, which relies on cottage industry while it is also centralised and organised though the Chios Mastic Growers Association.

The production of mastiha, an ancestral practice, unaltered over time, is a family occupation that requires laborious care throughout the year, and in which men and women of all ages participate on equal terms. Tasks are divided across genders and ages. The culture of mastiha represents a comprehensive social event, around which networks of alliances and mutual help have been established in society. Traditions and legends survive in the vernacular language, some of religious nature. The knowledge for growing mastiha follows certain rules and traditional characteristics, which ensure its authenticity, while also promoting improvisation and individuality. The craft and local life still witness age-old traditions related to the production of mastiha, even if the cultivation and application of mastiha are constantly subject to innovation.

Mastic cultivation

Processes performed by the producers

Cultivation of new trees: The cultivation of new trees takes place during the winter, from beginning of January until mid-February. The producers cut branches from a male tree of good quality and plant them in depth of 40 to 60 centimetres. It is rather easy for a plant to be successful and it does not need special care in the beginning.

Pruning, cleaning, fertilization, and irrigation: Pruning of a tree begins on its third year and then takes place every year during the winter, from beginning of January until mid-February. The dry branches are removed so that the tree can become stronger and to facilitate air and sun supply for the trees. The wounds from the cut branches are covered with a substance (katrami) to proof them from microorganisms. Fertilization of the field takes place in January or February and the producers use ammonium sulphate when the soil is poor and potassium nitrate or calcium ammonium nitrate for red soil. An ecological fertilizer is beans (Vicia faba) which are planted in October. When they reach the time to bloom, they are plowed in order to stop their growth. Because of the bacteria staying in the nearly bloomed beans, the soil becomes rich in nitrogen, which is essential for the growth of the mastic trees. Young trees do not need water. Irrigation starts after the first year of the tree and it takes place two, three or four times per day depending the weather conditions. The older trees are resistant to drought. It is important to note that persistent humidity can damage the trees to the point of drying and become sensitive in infections.

Cleaning the soil: At the end of June until beginning of July, producers clean, level and press the soil under the trees. Then the soil is covered with white clay so that the mastic resin that will fall will stay clean.

Kendima (embroidering): Kendima (as it is called in Greek; embroidering) takes place in July and August. The producers create vertical or linear incisions on the bark of the tree. The incisions are 4 to 5 centimetres deep and 10 to 15 centimetres long. The number of the incisions depends on the size of the tree. Vertical wounds heal faster. After kendima, the resin is left 10 to 20 days to dry.

Collecting: Collection of the dried mastic resin takes place from mid-August until mid-October. Usually big mastic pieces of resin fall on the soil while mastic ‘tears’ remain and dry on the bark and the branches.

Sifting and Cleaning: Sifting helps to separate mastic gum from gathered dirt and leaves.

Cleaning with water: After sifting, the producers clean the gum with soap and plenty of water. Producers that live in a village near the sea prefer to go to the seaside to clean the gum. It is easier in that way to separate them because the salty water keeps the dirt and leaves on the surface of the water while the mastic gum stays at the bottom of the basin.

Tsimbima (pinching): Tsimbima (as it is called in Greek; pinching) is the cleaning of the mastic gum with special knives in order any last dirt attached to the gum. It is performed by women.

Classification: Producers make a first classification of the mastic gum and mastic gum is sent to the Chios Mastic Growers Association.

Processes performed by the Chios Gum Mastic Growers Association

General processing upon arrival of mastic: When the Association receives mastic gum from the producers further classification takes place, according to size of the gum. In general, they separate the pittas (usually large, round pieces), chondri (‘fat’ pieces) and psili (thin pieces). In this way, they store the gum and gradually process it further depending on the demand. Sifting, cleaning with water, drying, weighting, tsimbima (pinching) take place.

Chewing gum production: For the production of mastic chewing gum, first the mixture is prepared which is made out of mastic, sugar, butter, corn flour, and water. The ingredients are placed in the blending machine to produce the mixture. After 15 minutes, the mixture is taken out of the blending machine and it is placed on a marble counter. Then it is formed to pieces of maximum height 3 centimetres and left to cool. After cooling, the pieces are transferred to the press and engraving machine where they are press and gum dragees are formed. At the end, the dragees are cut and put in the candy machine to create their coating made out of syrup.

Mastic oil production: Mastic oil is produced through distillation.

Mastic incense production: Incense is produced with a special press machine that crushes mastic gum of lower quality.

Packaging: The Chios Gum Mastic Growers Association where also responsible for packaging their products. For this reason, they also have packaging machines to wrap the products, and printing machines to create the covers of the products.

Marketing: The Chios Gum Mastic Growers Association took charge also of the marketing strategies for the promotion of the mastic products. In [62] mentioned that the choice of photographic material and design that the Association selected reflects has a cultural meaning for the Chios society.

Thematic tours on mastic cultivation

Destinations – The Mastic Museum of Chios

The Chios Mastic Museum is located in the Mastichochoria (literally: mastic villages), a group of medieval villages in Southern Chios, the only site in the Mediterranean where the mastic tree, or Pistacia lentiscus var. Chia, is cultivated; called by its generic name of skínos in Greek, this is an endemic variety of pistacia plant from which mastíha (gum mastic) is produced.

The Chios Mastic Museum aims to showcase the production history of the mastic tree’s cultivation and the processing of its resin, which it integrates into the cultural landscape of Chios. Through the prism of UNESCO’s inclusion of traditional mastic cultivation on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2014, emphasis is given to the diachronicity and sustainability of this product of Chios.

What is on display:

The permanent exhibition centres on Chios mastíha as a unique natural product. The introductory module provides information on the mastic tree and mastíha, its resin, which in 2015 was recognised as a natural medicine. The first module presents the traditional know-how of mastic cultivation. The second module focuses on how managing the cultivation and its produce shaped the agricultural landscape and the settlements of southern Chios and the Mastichochoria historically. The third module is dedicated to mastíha resin’s cooperative exploitation and processing in modern times, which marks an important chapter in the productive history of Chios. Particular mention is made to the uses underpinning why mastíha has a worldwide presence today. The museum experience is completed in the outdoor exhibition, where the public comes into contact with the plant itself and the natural habitat it prospers in.

Destinations – Mastic Villages

Every Mastichochori (mastic village) organised the agricultural space around it differently, according to the site where the village was located and the natural resources in the environs. Villages were constructed in flat lowland areas with access to water sources, located far from the sea. Usually they were built in small valleys suitable for systematic cultivation.

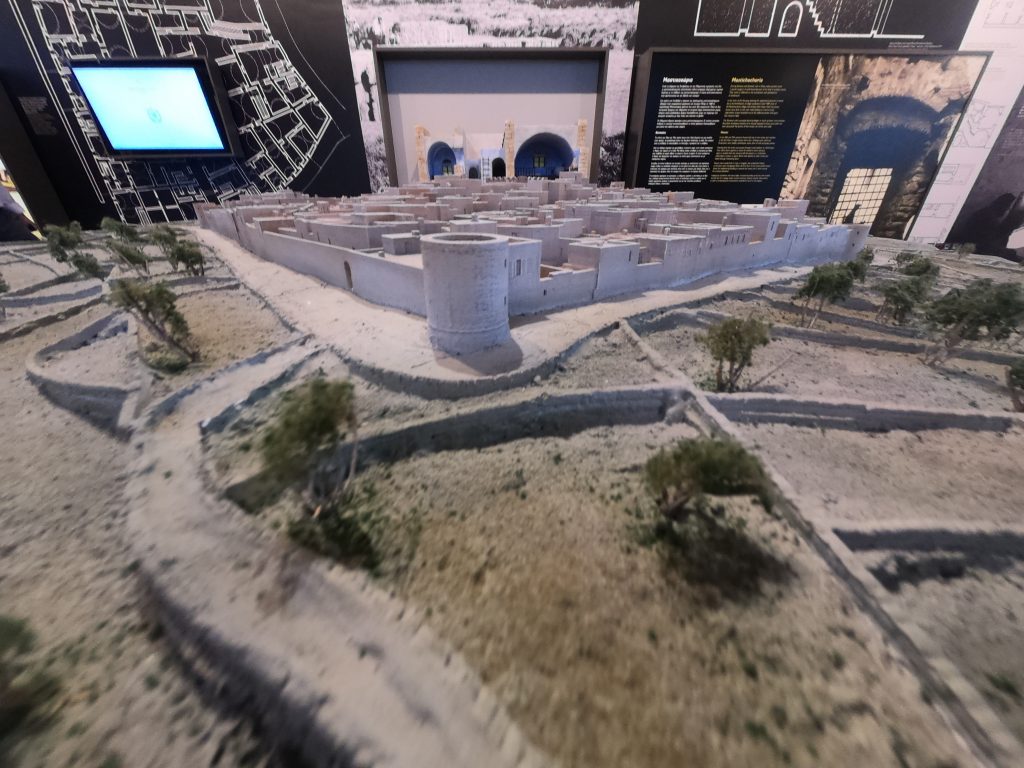

Until 1400 most of the Mastichochoria had been already shaped. The gates of the walls surrounding them opened and closed at predetermined times. Villagers left in groups early in the morning and returned in groups at dusk. The tower built for defence purposes was at the centre of the village. It was the largest and tallest building, the final refuge in case of a raid by pirates. The streets linking the central square of the tower with the gates of the walled village were few and narrow. From them branched out other streets, even narrower and leading to cul-de-sacs with small houses.

In the time of Ottoman rule, thanks to the privileges given to the inhabitants of Chios, the villages became densely populated. Residences grew in size and were enriched with decorative elements. Yet, houses located in villages always functioned as units of production and processing of agricultural produce and subsistence needs. The public spaces and the workshops functioned in order to serve the needs of the community.

Villages architecture

During this long-lasting period, the skinos trees were the dominant feature of the landscape. The villages, the pathways and the rural constructions, the farm fields and the pasture grounds were all used uninterruptedly.

Every Mastichochori (mastic village) organised the agricultural space around it differently, according to the site where the village was located and the natural resources in the environs. Villages were constructed in flat lowland areas with access to water sources, located far from the sea. Usually they were built in small valleys suitable for systematic cultivation.

Until 1400 most of the Mastichochoria had been already shaped. The gates of the walls surrounding them opened and closed at predetermined times. Villagers left in groups early in the morning and returned in groups at dusk. The tower built for defence purposes was at the centre of the village. It was the largest and tallest building, the final refuge in case of a raid by pirates. The streets linking the central square of the tower with the gates of the walled village were few and narrow. From them branched out other streets, even narrower and leading to cul-de-sacs with small houses.

In the time of Ottoman rule, thanks to the privileges given to the inhabitants of Chios, the villages became densely populated. Residences grew in size and were enriched with decorative elements. Yet, houses located in villages always functioned as units of production and processing of agricultural produce and subsistence needs. The public spaces and the workshops functioned in order to serve the needs of the community.

Houses architecture

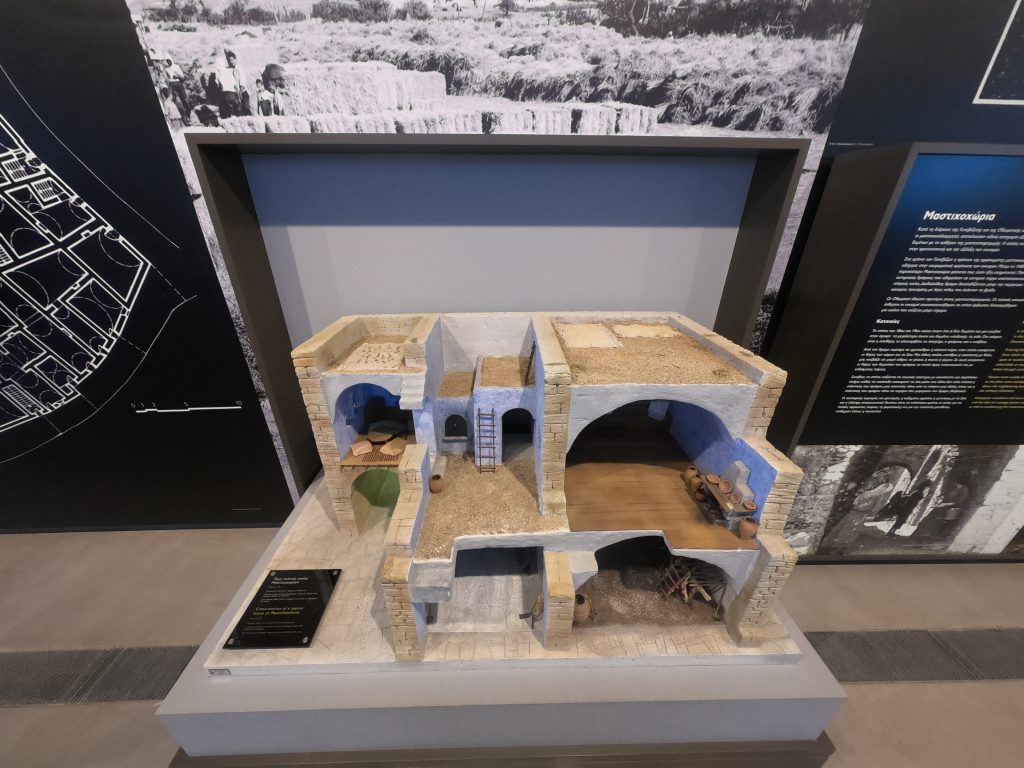

The houses were built from stone and a binding agent. In order to construct a storey, stone or wooden beams were essential. Balance was ensured with the use of carved beams, made out of wood or metal, free-standing or embedded in walls. Even though buildings support each other, as in most cases they share sidewalls in terraced building, it is possible to see joint between houses, as proof of non-concurrent construction.

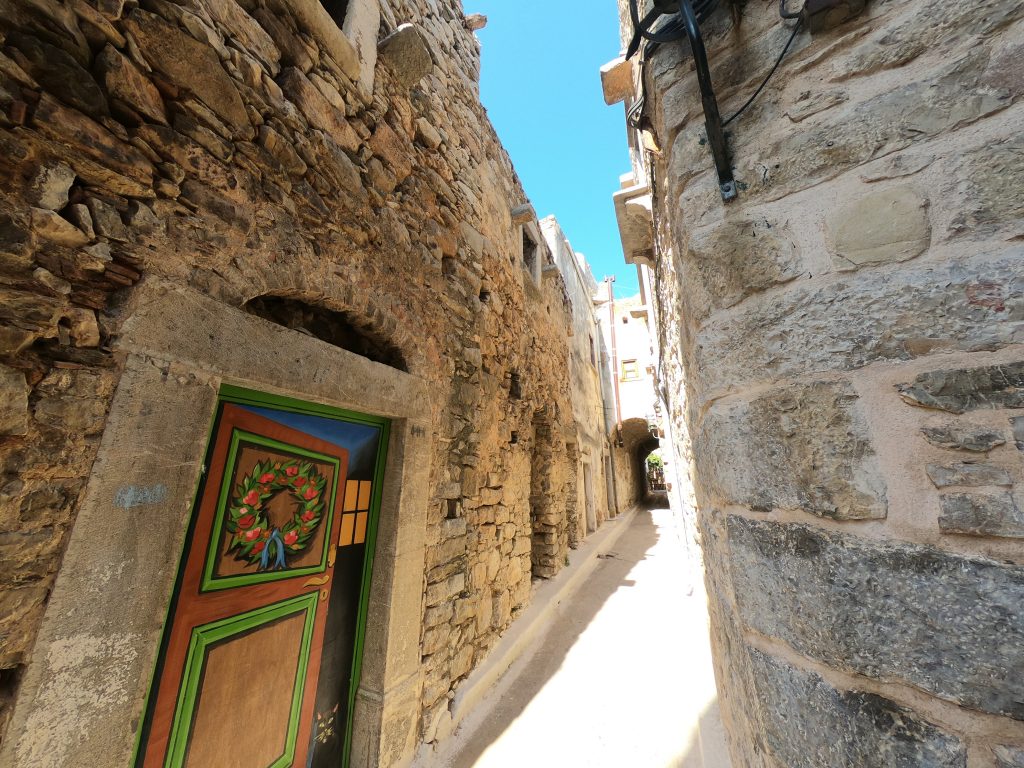

The buildings were usually crooked and complex in shape, as the building blocks intruded in each other. Quite often, a storey extended over the rooftop of the building next door, through an arch that created a passageway.

The interior of the house, although restricted in size, was by no means Spartan. Wooden cupboards and shelves adorned the walls, while a wooden elevation was used as a bed in the room where the whole family slept. The floor was usually covered with “astrakia”, a kind of hydraulic lime with a smooth texture, also used to cover rooftops. In a few cases, floors were covered with stone tiles, while in houses that are more recent the bedrooms have wooden floors. Sometimes we also see decorated pillars. Window frames were especially decorated, and sometimes-characteristic seats were created in front of the windows, matching the thickness of the wall.

Inside a mastic house

Olympoi

The village is located in a lowland zone. Just outside the village, limits there are orchards, and the skinos plantations are located at higher ground.

The village is walled. There are turrets at the corners of the wall. Two gates open to the two central roads of the village leading to its centre, the tower, where they converge. Houses have been built along the wall, and so there are windows on it.

The village roads are narrow and labyrinthine. The houses have two storeys by now, and often rooms extend outwards over the street. The dominant colours are those of the local rocks.

Mesta

Purgi

Elata

Indigenous Crafts

Xysta – Purgi

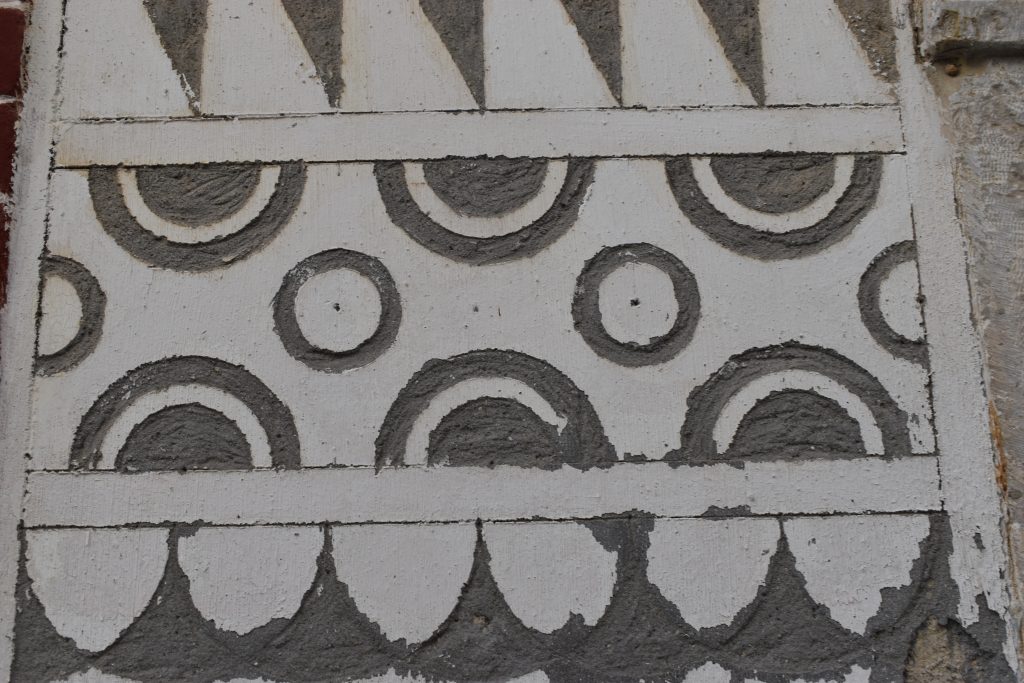

The fronτ part of the houses present a special decorative perception, the ”ksista”, which are unfolding to superfluous horizontal patterns with black and white geometrical shapes. They begin mostly from halfway the doors and rarely above it. The patterns consist of squares, rhombus, triangles, most of which depict flower bouquets, sea cranes, tree branches, long narrow tree leaves and many others. Ksista have as a basis a durable lime coating, onto which while being still fresh, are being carved with caliper, ruler and forks the various patterns. After the scraping of the exceeding material, the outline of the patern takes dark colouring and as a total it presents a smooth texture anaglyph. It is considered that this technique displays italian or either oriental roots, the patterns though are prototype.

(source: Chios Tourism Organisation)