Have you ever wondered how the pattern in splendid silk fabrics is created? Or asked yourself how many steps are involved in the process? The answer is Jacquard weaving. But what does that entail exactly? Haus der Seidenkultur takes us along the journey of Jacquard.

The original draw loom

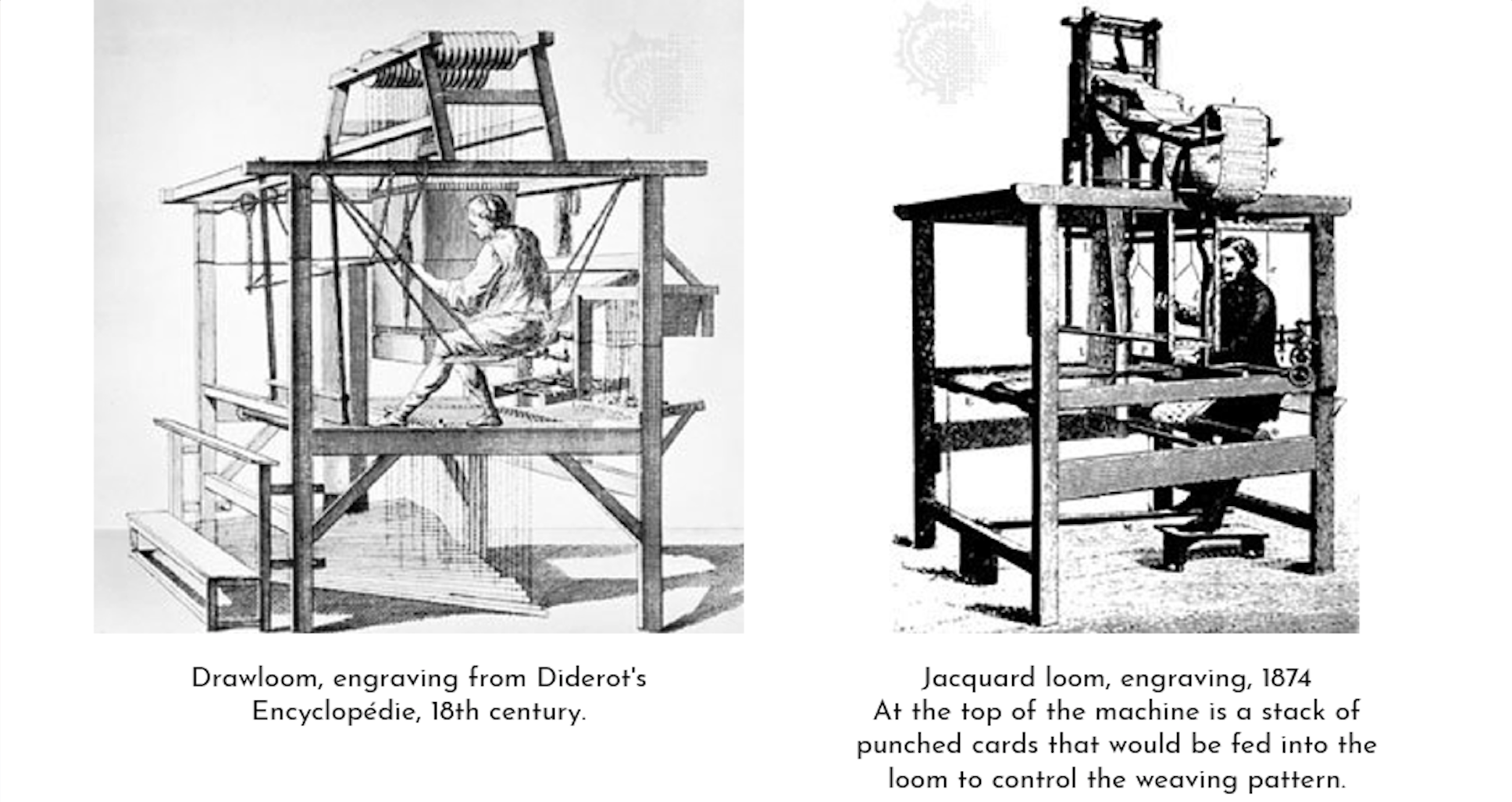

The story behind Jacquard weaving dates back to China in the second century B.C., when the first draw loom was invented for silk weaving. In order to weave an intricate silk pattern or picture, it is necessary to raise or lower each of the sometimes thousands of warp threads individually to form a shed through which to pass the shuttle.

At that time, this was done by a so-called draw-boy who sat on top of the loom. Every single row of weaving required different warp threads to be raised or lowered and consequently the production process was very slow and required meticulous attention. This was the main reason why over a period of three-quarters of a century several inventors turned their minds to constructing a better system.

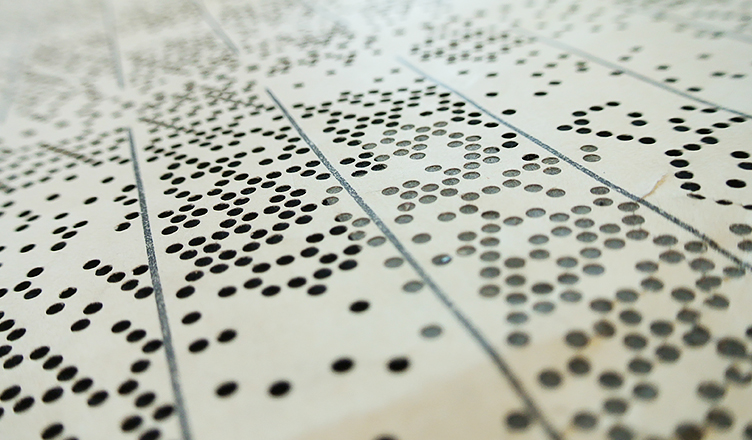

Basile Bouchon improved the traditional draw loom in 1725, when he substituted an endless band of perforated paper for the bunches of looped strings previously used. In 1728, Jean-Baptiste Falcon used perforated cards manipulated by a draw boy. Jacques de Vaucanson combined these two inventions in 1745, placing his machine where the pulley box had previously been. Finally, the breakthrough came from Joseph Marie Jacquard who took these inventions one step further to speed up the process and remove the need for a weaver’s assistant.

Developing Jacquard weaving

Joseph Marie Jacquard was born into a master weaver’s family in Lyon France in 1752. He spent most of his time helping in his father’s workshop gaining experience in the various facets of weaving rather than going to school. Some say that he actually worked as a draw boy. After the death of his father in 1772, Jacquard half-heartedly took over his business. However, he must have started his late career in silk loom-making around 1799.

Jacquard’s dream was to build a revolutionary new machine for weaving pictures into silk brocade. He had an innate talent as a craftsman and inventor, carving the pulleys and other components himself. Other master craftsmen and businessmen obviously had faith in him because he was offered financial support to keep working on his machine until it was perfected. He finally took out a first patent in December 1800, which is registered in the archives in Lyons for a “machine designed to replace the draw boy in the manufacture of figured fabrics”. The patent for his brocade loom, with which he is most known for, was finally granted in 1804.

The draw-boy is replaced

On Jacquard’s loom, the weaver controlled the pattern with the help of a punched card system. Each punched card was pressed once against the back of an array of small, narrow, circular metal rods. Each rod controls the action of a weighted string that in turn controls one individual warp thread. If the rod encountered solid cardboard, the rod would not move and the warp thread stayed where it was. If the rod went through a hole then the warp thread would be raised to form part of the shed. The pattern or picture was embodied in an endless string of cards which were advanced one at a time by the weaver depressing the treadle of the loom.

Fabulous ornate silk fabrics could now be woven much faster. Napoleon and his wife visited Jacquard’s workshop in 1805, having previously decreed that his ceremonial garments be woven by the silk weavers in Lyon; no doubt on a Jacquard loom. He also declared that Jacquard’s loom should be public property, in return for which Jacquard received a handsome pension. Jacquard looms soon spread around Europe, including to Krefeld in Germany.

Moreover, Jacquard’s invention has influenced industries beyond crafts. The use of replaceable punched cards to control repetitive operations is considered important for the development of computer hardware. Jacquard’s idea of punched cards to control a machine was taken up by Babbage and Ada Lovelace and incorporated in his “Victorian” computer.

At Haus der Seidenkultur in Krefeld, Jacquard looms originally dating from 1868, just 30 years after Jacquard’s death, can still be seen in action in the original workplace. Experts are still demonstrating the preliminary skills required to prepare the harness for a Jacquard loom and transfer an ornate picture to fabric via point paper and punched cards. The Mingei project aims to preserve and represent the knowledge and skill of these crafters.

Written by Cynthia Beisswenger of Haus der Seidenkultur

Sources:

Encyclopaedia Britannica Ltd., London, Copyright 1957

Jacquard’s Web, James Essinger, Published by Oxford University Press, First Paperback edition 2007